The agricultural plantation had been abandoned for decades. Deserted shortly after the Republic of Congo (known as the ROC or Congo Brazzaville) declared independence from France, its empty warehouse, rusted equipment and encroaching vegetation embodied the stagnation of the country’s agriculture sector. Then in 2011, a new company arrived.

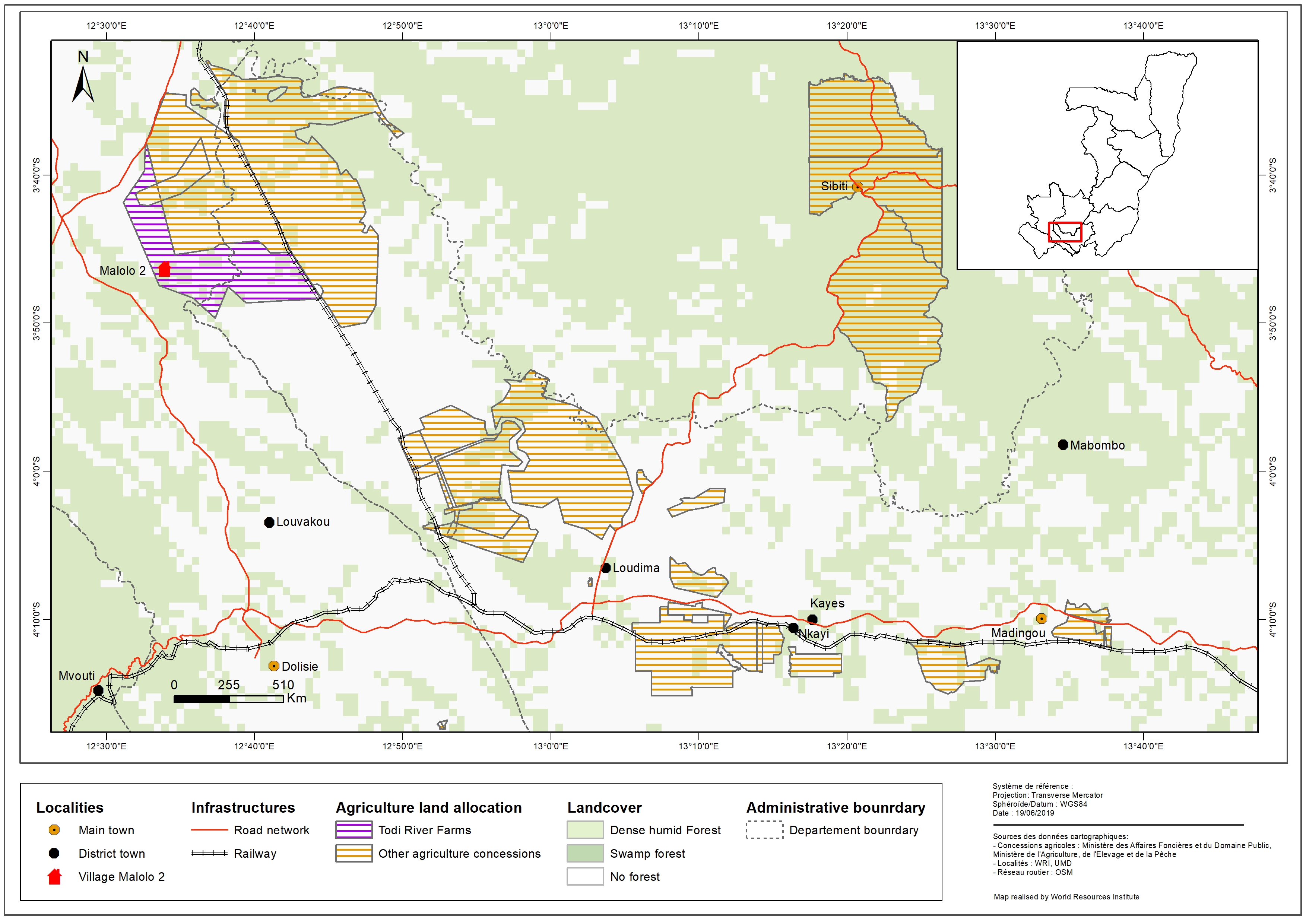

The South African company, which named the site Todi River Farms, had permission from the Congolese government to grow corn and other staple crops on the 40,000-hectare property. The only problem? No one had told the residents of Malolo 2, the village a few hundred yards down the road.

The village is now home to farmers and Babongo hunter-gatherers who depend on the land around them — not just agricultural plots, but also the surrounding forests and natural grasslands — for survival. When Todi River Farms set up shop, some residents found work there harvesting and processing the crops. However, these workers had no contracts (or, therefore, job security), and as the crops began to flow out of the plantation in trucks bound for nearby markets, Malolo 2’s other inhabitants didn’t see any benefits.

Malolo 2 may have a unique history, but its current predicament could afflict many other Congolese towns in the future. As the ROC strives to diversify its economy beyond the oil sector, which accounted for almost 80 percent of government revenue in 2011, the country is looking to attract investments and expand its agricultural industry. But as lessons from Malolo 2 demonstrate, it is critical that national government officials making decisions about land use consider local residents from the start rather than as an afterthought.

By bridging the gap between everyone who has a vested interest in the land — government ministries, private businesses and nearby communities — the World Resources Institute (WRI) and its partners are working to ensure that the economic growth the country needs will not come at the expense of the people or ecosystems that power it.

The farming frontier

As of 2010, about 63 percent of the ROC was covered in trees. The country’s forests form part of the larger Central African rainforest — the world’s second-biggest after the Amazon. Three-fourths of the country’s 5 million people live in its two largest cities, Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire, leaving most of the ROC’s land sparsely settled and underdeveloped.

The 2014 downturn in global oil prices revealed the danger in having so much money tied to one commodity, not to mention pinning economic hopes on a nonrenewable fossil fuel that is warming our planet.

“Less than 2 percent of Congo’s arable land is currently being exploited for agricultural activities,” says Jean Maurice Muneza, WRI’s regional coordinator for land-use planning in the Republic of Congo. “If you live in Brazzaville, you will see this for yourself, because people depend so much on imported products. Meat, rice, potatoes, wood — everything is coming from the outside. Which means the country also is losing a lot of money by importing these kinds of products.”

Historically, the rate of forest loss in the ROC has been low compared to other forested countries, likely due to the country’s low population and limited industry. For example, the much more populous Democratic Republic of Congo experienced almost 22 times as much tree cover loss in 2018. However, as tropical forests worldwide continue to disappear, remaining forests are increasingly in demand. This could soon make the ROC a new frontier for development — and forest destruction.

Better coordination starts at the top

Plans for how the ROC’s natural resources will be managed are usually made far from the lands in question and the people who inhabit them.

In the offices of Brazzaville, ministry staff sometimes rely on paper maps and draw GPS coordinates for new investments by hand. Coordination is minimal, with ministries that govern natural resources (mining, forests, oil, agriculture) housed in separate buildings scattered throughout the capital. To further complicate things, most ministries rely on their own maps and data sources rather than a common, centralized database. Computers are scarce, and limited access to technology and training on how to use maps and manage information is a chronic challenge among government employees.

A 2014 national law on land-use planning and development sparked new momentum to improve this situation. The ministry in charge of land use is playing a leading role in defining a vision for land use in Congo that would support the country’s sustainable economic development. There was just one problem: how to get started, particularly given the government’s lack of technical capacity.

“Planning without mapping is like navigating without a GPS,” says Antoine Goma, the director general of spatial planning within the national land-use planning ministry. Enter WRI, which has a long history of helping government agencies build publicly available information platforms, such as the Forest Atlases, that encourage more transparent and informed natural resource management. WRI worked with Goma and his colleagues to create a roadmap for what implementing the new land-use law could look like in practice. The first step: build capacity within the ministry itself to take this work forward.

In 2017, WRI established, equipped and began training a GIS unit within the land-use ministry. Thanks to a program of skill-building exercises, along with regular on-the-job training from Muneza and other WRI technical staff, the GIS unit members have compiled their own centralized, increasingly extensive database that will equip the ministry to review planned developments and avoid overlaps and conflicts. In the words of Thecle Moudiongui, a ministry technician, “I had never been trained on mapping … at the beginning we were at the zero level as far as GIS is concerned, but now we can say that our management can give us tasks and we can work without the help of WRI.”

Building off this success, WRI and the land-use ministry are launching an online land-use portal — the first of its kind in the region. The portal is a clearinghouse of information on land in Republic of Congo that includes geospatial data, sector laws and policies and eventually scenarios to orient future planning decisions. The portal will launch later this year, at which point WRI and the land-use ministry will encourage other ministries to incorporate it into their planning processes — for example, using it to confirm that a new agricultural concession isn’t designated for a plot of land already slated for conservation.

“When we think about capacity-building, people tend to focus on trainings,” says Lauren Williams, senior manager of WRI’s Central and West Africa Forests program. “What we’ve learned is that skill-building happens best outside of a training workshop as partners apply what they learned every day. It takes time and commitment to build the technical capacity that Congo needs to implement a better vision for its land that will also not overlook people such as the residents of Malolo 2.”

“Establishing the GIS unit and setting up this portal are positive steps, but a lot of work is ahead to make sure future decisions create opportunities for people that don’t come at the detriment of Congo’s forests and wildlife.”

Community protection on the ground

How did the situation with Malolo 2 arise in the first place? As with many similar conflicts elsewhere, it stemmed from a lack of understanding of what’s really happening on the ground, and the limited obligation of authorities in Brazzaville to consider local residents when siting new developments — exactly the type of uninformed decision-making that WRI and the land-use ministry hope to correct with the launch of the land-use portal.

Malolo 2 first appeared on WRI’s radar through its work with Cercle des Droits de l’Homme et de Développement (CDHD), a Congolese NGO that advocates for the rights of marginalized people, including indigenous groups and other rural communities. Noting the absence of adequate social and environmental protections within the agricultural sector, WRI and CDHD designed a study to understand how the expansion of large-scale agriculture is impacting rural communities in the ROC. CDHD chose two sites to investigate. One site, in the forest-rich north of the country, is a community in the middle of an oil palm concession; the other is Malolo 2, located near the small, southern Congolese city of Dolisie.

“You have a camp for your workers. That camp is electrified, yet our whole village is in darkness.”

With financial and technical assistance from WRI, CDHD spent six months interviewing community members, company employees and government officials and monitoring both sites. Through the Malolo 2 study, they learned that no environmental impact assessment had been done for Todi River Farms. There was no wastewater treatment facility. The local government was not consulted before the company arrived; all the arrangements were made in Brazzaville without informing local officials. And perhaps most importantly, there was very little communication between the company and the village.

“There was a conflict between the company and the community about the land,” says Alvin Koumbhat, CDHD’s program coordinator. “Since that land was given to the company, the community had no more rights to go and use those spaces.”

CDHD published a report summarizing what they learned, emphasizing the lack of social and environmental safeguards that were in place to protect the rights of the community. This publication — and CDHD’s outreach around it — spurred Todi River Farms to act.

“The company started to talk with the community, and asked them what they want,” Koumbhat recalls. “They discussed, and said ‘You have a camp for your workers. That camp is electrified, yet our whole village is in darkness.’”

Today in Malolo 2, many of the homes have solar panels provided by the company on their roofs, which provide enough electricity to power a lightbulb at night or charge a cell phone. The company has installed a water pump in the center of the village, reducing the amount of time women and children must spend collecting water for their households. It has built a health clinic and donated medical supplies, as well as textbooks for the nearby school. And it has designated a plot of communal farmland maintained by Todi River Farms with crops available for villagers to use or sell for profit.

These community benefits have helped improve the relationship between Todi River Farms and the village. However, the situation remains complicated. Some of the village’s sacred sites, which are used for religious rituals, remain on the land slated for agricultural production by the farm. Because these areas aren’t currently being cultivated, villagers are still allowed to visit them, but there is no guarantee that this will continue.

To lay the groundwork for protecting the customary land rights of Malolo 2’s residents, WRI and CDHD worked with the community to create a map of their village, the surrounding land and which places they use for which activities (including sacred sites). This map is the first step they need to continue to advocate for their rights, and maps such as these should also inform the national land-use reform process when the time comes. The latter step is critical to ensure that local and indigenous communities are not just dependent on the whims of private sector companies who set up shop in their customary lands, but that their rights can be proactively recognized in planning discussions.

Next steps

While Malolo 2 has seen some improvements in its relationship with Todi River Farms, for every Malolo 2 there is a village like Mapati, also in southern ROC, whose residents recently discovered their village was in the middle of a newly created logging concession. As the trees around Mapati are cut down, its residents continue to live without power.

To reform the country’s land-use system by adequately protecting community rights while supporting sustainable economic development, change must come both from the top down and the bottom up.

“This is a key moment for the Republic of Congo,” says Williams. “As the country makes progress on its national land-use plan and diversifies its economy, it has the opportunity to protect its lands and people from exploitation at the outset and prevent more challenging situations later on.”

About the Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE)

The U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) CARPE program supports initiatives to improve the management of the Congo Basin’s biodiversity and natural resources. Since 1995, the program has invested millions of dollars in protecting the massive forest sometimes called Earth’s “second lung” while providing local people with economic alternatives to overexploiting it.

CARPE is implemented in collaboration with African Parks, African Wildlife Foundation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the University of Maryland, the Wildlife Conservation Society, World Resources Institute, World Wildlife Fund and other partners. Learn more.

Video clips at top of page: drone footage of Sangha River in northern Republic of Congo; staff from WRI and the ROC’s land-use ministry examine a map of the country in the office of the GIS Unit in Brazzaville; water drips from a pump recently installed in the village of Malolo 2; Todi River Farms workers load sacks of corn onto a truck; residents of the village of Mapati examine a map they produced to illustrate which places around their community they use for subsistence, economic and cultural purposes; drone footage of road near Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in northern ROC; a woman makes moambe (palm butter) out of oil palm nuts in Mapati. Drone footage credit: Forrest Hogg/WCS; all else credit: Molly Bergen /WCS/WWF/WRI.